As I’m sure we’ve all heard by now, a little over a week ago Tommy Ramone, the last of the original members of the Ramones, died. A few days later, I was asked if I wanted to write something about the Ramones and their influence. I was a bit hesitant, wondering what I might say about the Ramones that hasn’t already been said by people more qualified than me. Despite their early years of obscurity lugging their guitars around New York City without cases or in shopping bags—a good way to remember them—there is now no more iconic image associated with rock music than that of the Ramones logo stamped on countless black T-shirts. The Ramones are also the subject of numerous books and films, including the documentary End of the Century (2004), many of which do an admirable job of recording Ramones history.

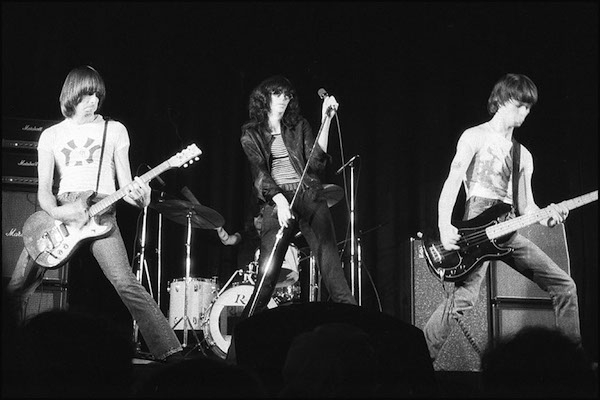

"Ramones 30081980 10 800" by Helge Øverås

Unfortunately, amid the recent punk rock nostalgia, we’ve also witnessed some anesthetized or mangled versions, which seem to forget that the Ramones injected horror themes into their music, seen in “Chainsaw” or in the title of their live LP, It’s Alive. As Johnny, legs spread, hammered the down stroke, driving the music into our brains, something terrifying emerged from the netherworld of the scene they, along with a select few like Richard Hell or Television, embodied, a specific moment headquartered at CBGB and Max’s Kansas City, that re-conceptualized rock and youth culture post-Vietnam.

But I was too young and living in the wrong city to be part of the ’77 CBGB crowd. My introduction to the Ramones came in the early 80s, and while we felt right on the heels of first wave punk rock, it turns out we were already way behind. The Ramones had played CBGB an insane 74 times by the close of their first year as a band, 1974. I was just 6 years old! And once I did discover punk rock, while we all thought the Ramones were cool, my friends and I jumped to the hardcore bands that had by then taken over the underground music scene: Dead Kennedys, Minor Threat, Circle Jerks, Subhumans. Bad Religion, Adolescents. These bands voiced our disillusionment with abuses of power and general conformity, as well as our sense of feeling out of step with mainstream culture, a prominent theme in the Ramones that I somehow hadn’t recognized.

So even though these bands were the children of the Ramones, Bad Brains, in fact, took their very name from a Ramones song, "Bad Brain", and I dressed like I walked off the cover of the Ramones debut LP—black leather jacket, beat up Converse, and jeans worn at the knees—I didn’t fully get it, that is, until I heard a live version of “Pinhead" and suddenly recognized in the sped up, razor sharp guitar and lyrics about rejects the girls of rock lore could never go for the ingredients essential to subsequent versions of punk rock. While it took hearing the Ramones at their most aggressive to get my attention, it didn’t take long before I began to appreciate all of their work, which I came to view as an important reimaging of rock and roll. Henry Rollins went so far as to suggest that the Ramones “rescued . . . rock & roll.”

On a personal level, no Ramones means no Germs, no Black Flag, and me lost to the likes of 38 Special (if you don’t recognize that group, thank the Ramones). Note that Rollins doesn’t limit the Ramones to the punk subgenre but rather claims their place within the lager trajectory of rock and roll. Musically, the Ramones combined the Beach Boys and The Shangri-Las with the more aggressive tendencies of MC5, New York Dolls, and the Stooges. The leather jackets invoking 1950’s delinquency extended the pairing of rebellion with rock music. They broke new ground, then, by looking back past the 20 minute guitar solos of overproduced acts. The Ramones countered with stripped down pieces in 4/4 time that revived rock’s fading visceral drive, leaving behind a blueprint, an approach to the art of making music that has and continues to influence numerous bands.

The basic approach was simple, just play. The Ramones were known for short songs that Tommy described as “to the point,” sonic ear bleeders in the two minute range, their early sets clocking in at under 20 minutes. They showed us that shows were better than concerts, replacing the strutting lead singer with a lanky, painfully shy frontman who just sang. No grand production nor self-indulgent interjections. Simple and to the point but not lacking in substance; they addressed war and poverty. The Ramones just played, over 2000 shows. Some of the venues would eventually get bigger, but the Ramones remained one of the few bands where the locale didn’t change much in terms of how they played, always “to the point.”

The Ramones also incorporated a sense of humor, though not the humor of 70’s variety hour TV. Their humor was often dark, campy, or just plain weird, as in “The KKK Took My Baby Away,” an absurdist Beach Boys scenario where Joey’s girlfriend gets kidnapped by the KKK en route to California. There are two versions of the story behind the song, one suggesting Joey wrote it after Johnny, who had an odd interest in to Hitler, stole his girlfriend (not all things were perfect inside the Ramones) and another claiming Joey wrote it in response to losing a black girlfriend. In either case, the humor allows Joey to confront hurt but without falling into self-pity. A similar oddball, at times sick sense of humor made its way into the music of Jello Biafra and the Circle Jerks and other bands attempting to address the absurdities of the cold war and late capitalism, or the cruel fate of being born a pinhead..

At the same time, the Ramones didn’t shy away from the ugliness they confronted in their city or their mirrors. In their music, (Beach Boys noir?) beautifully tanned California girls figured only as sources of rejection. The leather jackets, shabby hair, ripped jeans, and dirty tennis shoes didn’t glam up the band but rather accentuated their anti-teen-idol qualities. They ingeniously tapped into the detritus of an increasingly disposable world, the discarded cultural products out of which punk rose, safety pins and all (thank you, Richard Hell). While the Ramones had upbeat songs, this was also the music of urban decay or, as in “Chinese Rock,” the drug addiction to which Dee Dee fell prey. The Ramones second single, “53rd and 3rd," written by Dee Dee about male prostitution, hustling that Dee Dee knew from firsthand experience, and insecurities about masculinity, ends in violence. Another horror story, horror which, again, they balanced with humor to produce music out of trash culture, which against all odds, somehow survived beyond its host, beyond the four men who created for us a place inside their songs, their shows for the all the awkward, disposable outsiders who now pay homage to the band who not only saved rock and roll but also saved us.

El autor es catedrático del Departamento de Inglés de la Facultad de Humanidades de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Río Piedras, y un colaborador invitado de Diálogo Digital.